Planets Without Water Could Still Produce Certain Liquids

By Science Correspondent

Water is essential for life on Earth. So, the liquid must be a requirement for life on other worlds. For decades, scientists’ definition of habitability on other planets has rested on this assumption.

But a new study from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) challenges that idea.

What if a completely different kind of liquid—one that doesn’t involve water at all—could support life-like chemistry?

Researchers have discovered that ionic liquids, which are made from salts, might be able to exist naturally in environments where water can’t survive.

The findings, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, show that these unusual liquids could form from sulfuric acid and nitrogen-based organic compounds—ingredients that are already known to exist on some rocky planets and moons.

Even more surprising, these liquids remain stable in extreme heat and very low pressure, where water would instantly evaporate or freeze.

What Are Ionic Liquids?

Ionic liquids are a type of salt that stays in liquid form at relatively low temperatures—often below 100°C (212°F). Unlike water, they don’t easily evaporate and can remain liquid under harsh conditions.

In this study, MIT researchers found that combining sulfuric acid with certain nitrogen-containing molecules produced a long-lasting, stable liquid. Sulfuric acid can come from volcanic activity, while the nitrogen-based compounds have been found on asteroids and other planets, suggesting this type of chemistry could occur in many places.

“We usually assume life needs water because that’s what life on Earth depends on,” says Rachana Agrawal, lead author of the study. “But if we think more broadly, what’s really needed is a liquid environment where chemical reactions can happen. That could include liquids like the ones we discovered.”

A Discovery by Accident

Interestingly, this breakthrough started with research focused on Venus.

Agrawal and her colleague Sara Seager, a planetary scientist at MIT, were working on ways to collect and study samples from Venus’ thick, acidic clouds. They were testing how to remove sulfuric acid from samples without destroying any organic compounds that might be present.

While experimenting with mixtures of sulfuric acid and the amino acid glycine, they noticed something odd. After most of the acid evaporated, a thin layer of liquid remained.

It turned out this was a new substance: an ionic liquid, formed through a reaction between the acid and the organic molecule.

That unexpected result sparked a bigger question: could these liquids form naturally in the real world?

Testing the Theory

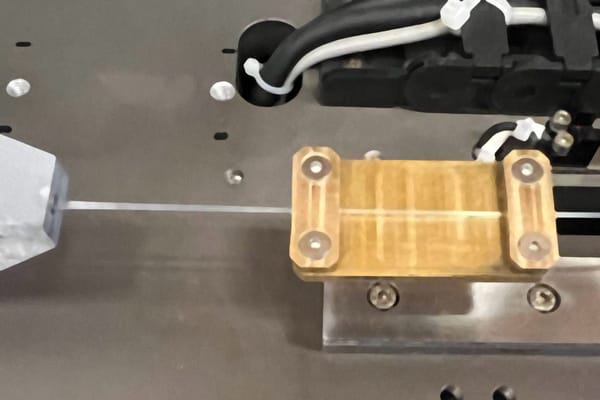

To find out, the team mixed sulfuric acid with over 30 different nitrogen-based organic compounds under a variety of conditions. They even applied the mixtures to basalt rock, which is found on volcanic surfaces here on Earth and on many other rocky worlds.

No matter what combination they used, the ionic liquids kept forming—even at temperatures up to 180°C (356°F) and in extremely low-pressure environments.

“We were amazed,” says Seager. “Whatever we tried, the ionic liquid still formed. Even when the acid soaked into the rock, the liquid stayed behind on the surface.”

What This Could Mean

On Earth, ionic liquids are typically made in labs and used in industrial processes. They rarely occur in nature—except in one strange case, involving a chemical reaction between two species of ants.

But this study suggests they might form naturally under the right conditions, especially in places with volcanic activity and the right organic ingredients.

The next step for the research team is to explore how biological molecules behave in these liquids—and whether they can support the kinds of complex chemistry that life requires.

“We’ve opened a whole new direction for research,” Seager says. “It’s exciting to think that chemistry we thought only existed in labs might actually be happening out there in nature.”